Teaching

For the first two weeks at least, the feedback in my (very frequent) observations was ‘you are going much too slowly. You need to speed up!’ Having worked for over five years in other schools, I’d become adept in the ‘explain it slowly three times and check everyone understands before doing anything,’ and at Michaela that is completely unnecessary – with the expectation for 100% sitting up straight and looking at the teacher, they get it first time, every time.

I was also spending far too much time eliciting information the pupils didn’t know – at Michaela, instead we tell them and then check they have learned it. So, if there is a word they haven’t learned I used to say ‘who knows what this word means?’ And if someone got close, try to elicit them to the right answer. Now, I say ‘woe means “intense sadness.” Annotate it on your booklet.’ And then, at the end of the lesson, I ask the class: ‘what does “woe” mean?’, along with the other new words we have encountered.

I’ve written at length about how we give feedback to help pupils improve their writing, but for me this was a totally new way of approaching looking at kids’ work. I’ve learned lots about the best way to explain how to improve, and when it is important to show exemplars to clarify trickier concepts.

I’ve worked on my ‘warm-strict’ balance. In a school with such strict discipline, it is especially important to explain why you are issuing a demerit or a detention – because you love them, because you want them to learn and succeed, and that issuing such a sanction doesn’t diminish your love for them as a human. I can’t emphasise enough how important it is at Michaela to show your love.

I’ve never taught from the front so much in my life, so I’ve had to improve my explanations. Luckily, I work with wonderful colleagues, and our weekly huddle where we annotate the lessons for the week has really helped me become clear on exactly what I will be explicitly teaching the pupils and how. This has been especially important for me with grammar, as I’ve never taught a single grammar lesson in my life. I am eternally indebted to Katie Ashford for spending countless hours going through the resources with me, and in particular for her eternal patience in always quickly answering my occasional panicked text message, which invariably reads: ‘is this an adverb or a preposition?’

Ego

Previously, I’ve been a bit of a praise junkie. I like to be told I’m great. There is no room for ego at Michaela – I’m bringing my A-game to every single day, and still have a such a long way to go to match up to the brilliant people I am surrounded by. It can be hard to see daily the distance between where you are and where you need to be, but being hung up on yourself just makes it harder. I’ve also had moments of panic, where I’ve thought: ‘I need to progress up the career ladder! Why did I quit an Assistant Head position? I need to have an impressive title and feel important NOW!’

Luckily, I’m able to find peace in the realisation that it isn’t about me – it’s about the school. The point isn’t me being brilliant and important, the point is all of us working together in the best way to serve our children. The ego gets in the way – kill it dead.

Purpose

I’ve written before about the intensity of the Michaela school day: no doubt, working at Michaela is hard! The difference is purpose: I’m not doing last-minute marking or planning, I’m not having stressful altercations with recalcitrant children or chasing up a thousand missed detentions: I’m preparing our year 9 units and improving our year 7 and 8 ones.

Reading my year 8s essays on Macbeth, who I’d only taught for a month at that point, was an emotional experience. Every single one contained more genuine engagement, impressive analysis, and originality of thought than any other essay on Macbeth I had ever read – including my previous year 13 class. I can’t take a single shred of credit for that, having only just arrived, but again it affirms my purpose: the sky is the limit for what these children can do, and it makes me want to do everything I can to see what is truly possible.

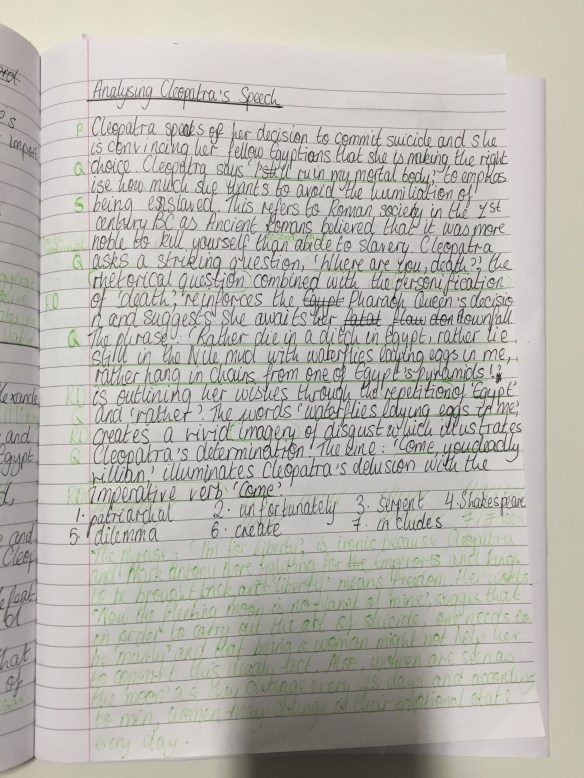

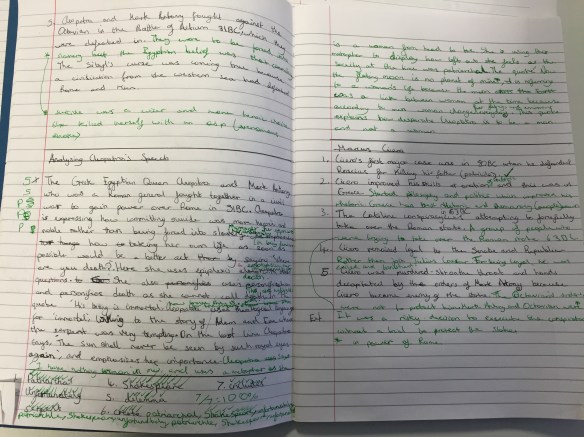

![FullSizeRender[1]](https://readingallthebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fullsizerender11.jpg?w=584)