While moving my blog from Squarespace to WordPress, I witnessed some worrying things. I was horrified to see the extent to which I had relied upon group work, philosophy circles and multimedia to engage pupils. I considered, briefly, expunging these articles from my blog. But I decided, ultimately, that it was more honest to leave them. I have, you see, been on a journey.

When I first met Joe Kirby, Katie Ashford, Bodil Isaksen and Kris Boulton in 2013 to write an e-book for Teach First starters, I was their polar opposite. While they talked about knowledge and instruction, I raved about student-led lessons and pupils’ personal interpretations. We had common ground only on curriculum choice: the one thing that united us was the idea that kids should be taught great literature. We were desperately divided on how to teach it.

By September 2014, Michaela Community School had opened, and I was still nay-saying in the corner. It wasn’t until Katie Ashford shared her pupils’ essays with me that I had the profound realisation: their way worked. My way did not work. With my way, some children thrived, and others were left hopelessly far behind. With their approach, Katie’s set 4 (of 4) year 7s were outperforming my set 3 (of five) year 10s.

Teacher instruction sounded terrifying. For one thing, I’d never done it or been trained to do it. What would I say? How on earth could I fill 60 minutes of learning time with… Me? In my head, teacher instruction was like a lecture, and in my experience lecturers would speak once a week, and have a whole week to prepare it. How could you possibly lecture six times a day?

But that isn’t at all what it is. When I first visited Michaela, I accepted the theory, but had no idea what to do in practice. Seeing it, I saw there was a lot more common ground than I had thought. In fact, even in the dark days of 2013, I might even have done a bit of teacher instruction myself.

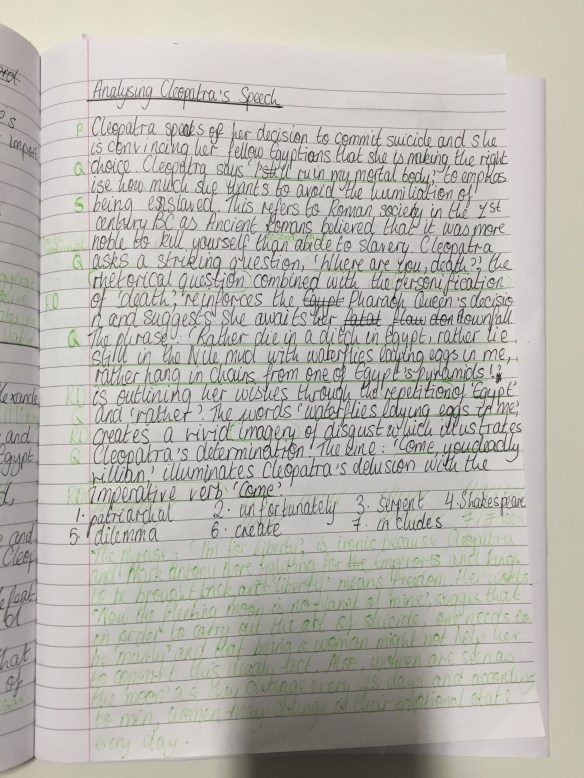

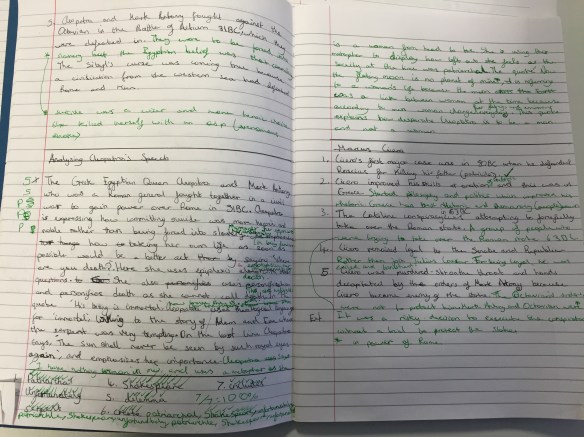

Teacher instruction is highly active, not passive. We explain, read, expand, yes; we also probe, question and test. We spend time writing out explanations and printing them up for pupil and teacher to read together. We spend time in department meetings discussing what we will teach and the key learning points we will be drawing out as we teach. The result is powerful: a highly engaging and dynamic classroom, full of pupils learning, answering questions, and recapping their prior knowledge. Visit Michaela and you see one thing very clearly: pupils love learning. They aren’t sitting in lessons bored, waiting for the next video clip or poster activity to engage them. They are answering questions, positing ideas, listening and annotating or taking notes, reading, reading reading; writing, writing, writing.

For a flavour of what teacher instruction looks like, watch year 8 annotating as Joe Kirby talks. Notice how he recaps on their prior knowledge throughout instruction – picking up on vocabulary they have learned, along with their prior knowledge:

Watch Olivia Dyer questioning year 8 in science. This is the start of a lesson, where she is recapping their prior knowledge. Look how many pupils have their hands up wanting to contribute! I always love visiting Olivia’s classroom – her manner is extraordinary: she is patient, quiet, calm and encouraging.

I love Naveen Rizvi’s excitement about the Maths as she carefully models for year 7, and engages the pupils every step of the way:

And finally, Jonny Porter’s expert use of a pupil demonstration to explain jousting to year 8, again recapping on their prior knowledge all the way:

![FullSizeRender[1]](https://readingallthebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fullsizerender11.jpg?w=584)