I’ve mentioned it two or three thousand times before, but I’ll say it again: I love my year 7 class. I’ve had many year 7 classes before, and I’ve found them all to be cute, lovely and well-behaved, but this year my year 7s stand out in a completely different way.

Part of this, I think, is due to my time-table: in previous years, I’ve taught 3 KS3 classes and then one KS4, plus a KS5. This year, I teach all exam classes, except for my year 7: they are my one and only class I am not pushing through a GCSE. They are my one and only class who are truly mixed ability (as in: all classes are mixed to some degree; these guys aren’t set yet).

Never before have I so appreciated the freedom which comes with teaching a KS3 class. I feel relaxed around this class; I take them on wild tangents when the conversation turns. I am excited to teach them, because I’m never completely sure where a lesson will take us. I’m flexible with my planning, moving lessons and assessments around due to their emerging needs because I don’t have any hard deadlines for them, or firm content to cover.

Right now, I’m loving teaching them poetry. Some genius teacher in my department created a beautiful scheme of work on war poetry, and it has been utterly joyful to teach. We began with a lot of context, which with the topic in question is not only fun and meaningful, but also pretty easy to teach, as usually students have great prior knowledge from primary school or history classes.

We studied Wilfred Owen in so much depth, students were commenting on different poems long after we had “finished” them, in their spoken and written responses. We moved through to female poets and conscientious objectors, and finished with Japanese poets on the atomic bomb.

Throughout the year, I’ve tried to mention in every class that my aim is for them to come up with interpretations. I have shied away from doing this with previous year 7 classes, as I’d found that their interpretations were almost always insane and had nothing to do with the text. With this class I decided to take a risk.

I’m not sure what has happened, but these students are already genuinely capable of coming up with interpretations which are not only valid, but also imaginative. I do a lot more whole-class discussion with this group, partly because the room layout discourages group work and circulation (I physically cannot get to about 6 students crammed into tight rows in a tiny room) and I want to speak with every student; this might have helped them to finesse their arguments as I always want evidence from the text, something their co-students perhaps aren’t so pushed about.

The most joyous moment of the course is hard to pinpoint. I thought it was the student who was so low-achieving at primary school she came in without a level, putting up her hand and giving an interpretation that was actually amazing, which sparked an important class conversation which went on for many minutes. That same student wrote an essay a week later and neglected to use a single quote or write about a single word from a single solitary poem. I despaired.

Having just marked their final assessment on this unit, there are too many “moments” to list, but I’ll mention a few.

The student above actually put in a number of quotes in her essay and used enough technical language to wind up on the cusp of level 3, which put a massive smile on my face. One of my level 4/5 borderline students suddenly grasped how to analyse language, which pushed her over the border to the magic 5, which I know she’ll be thrilled about because she works so hard in every lesson. A number of students wrote about ideas in their final assessment which we had never covered in class; one example is at the bottom of this post, but there were many who tried something new out.

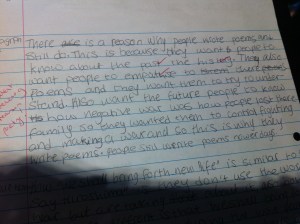

But what made me smile more than anything was the paragraph below, written by a student who also receives some intensive English catch-up.

What I loved about this was the joy in poetry that came from it. We’d not spoken specifically about the ideas she writes about, and given the parameters of the essay this came out of nowhere. But the genuine joy and love of poetry is so easy to see, and this is something which came through in so many students’ essays.

What I loved about this was the joy in poetry that came from it. We’d not spoken specifically about the ideas she writes about, and given the parameters of the essay this came out of nowhere. But the genuine joy and love of poetry is so easy to see, and this is something which came through in so many students’ essays.

My year 7 love poetry, with the same fervour my year 11 hate poetry.

It’s easy to see why though: my year 11 study the AQA “Relationships Cluster” of poems which has some lovely poems in it, but some really, truly dull ones. I’m constantly banging on about AOs and how they need to evidence their thinking in their essays in order to hit those AOs consistently throughout. I’m also forcing them to compare poems, which is nowhere near as effective as them doing it themselves (“miss, isn’t this like…”) and feeling really smart for thinking to do it.

My new aim is to build on this love and enthusiasm; to cling to it. Is it the normal year 7 excitement which will fade by the summer term, when new priorities come into play for them? Or is there a way to continue to invest them in what we are doing?

And how do I make this happen with all my exam classes?